July 6, 2012

Fiscally Spaced

By Brady Willett & Dr. Todd Alway

Central bank printing and excessive government borrowing are two themes that need no introduction. The U.S. consumer could become a source of stability for the financial world again (we’ll get to this). And oh how it hurts to wake up in the morning when you are old. What follows is the cornucopia of negativity that can be unfurled when looking at the financial world today – a world that is only out-daunted by one thing: how the world will look tomorrow.

Fed Heads Wonder What’s Next

As recently as February 2011 the U.S. Federal Reserve thought that U.S. GDP growth would be 4.0% in 2012 and 4.2% in 2013. Today these forecasts stand at 2.4% and 2.8% respectively. The Fed has also downgraded its employment and inflation expectations (assuming higher inflation is a good thing), and declared that it can do more to stimulate the economy. Should the U.S. unemployment figures not show material improvement soon, there is little doubt the Fed will act.

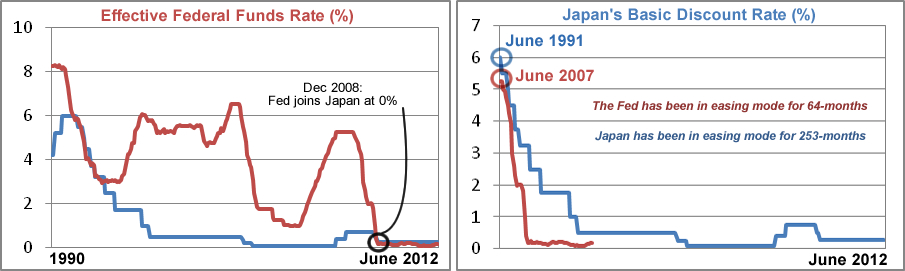

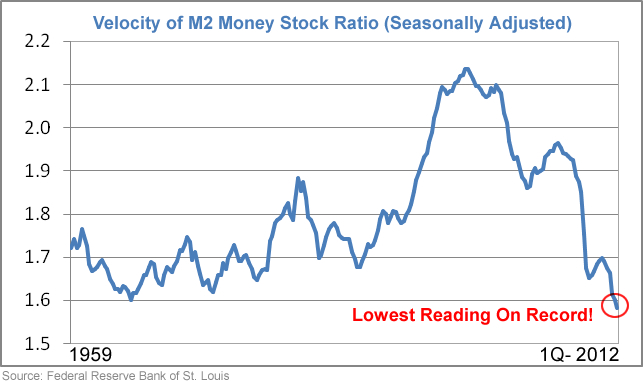

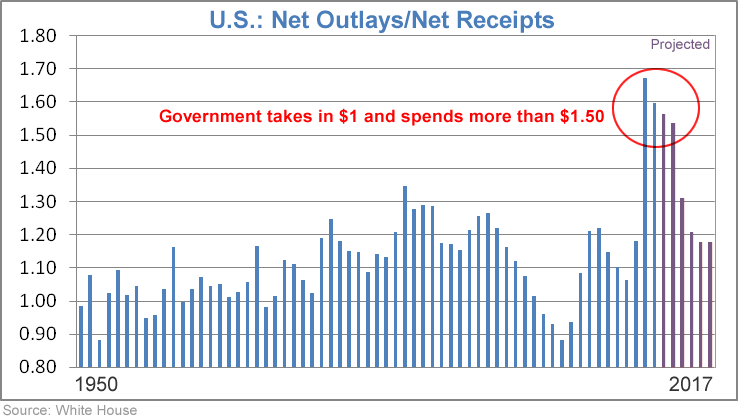

For all of the Fed’s bluster, the concept of diminishing returns has clearly entered the building. Coined a ‘liquidity trap’ by economists, the layman observation is that monetary policy has been used so often that it has lost both its teeth and its sense of purpose. To wit, the Fed said they acted in 2008 to save the financial markets, in 2009-2011 to try and stimulate job creation, and most recently (extending operation twist) because previous efforts did not work. The guiding light behind these aggressive interventions was, according to Bernanke, that the Fed must do everything in its power to avoid a Japanese or Depression-style meltdown. And yet here we are...

|

At what point do Bernanke and company conclude, at the minimum, that even more extreme measures must be saved for a rainy day? After all, interest rates are already at very agreeable levels, the money is out there, but even by the Fed’s own numbers, ultra-easy monetary policy is not being successfully transmitted into the real economy. Why waste ammunition at the rabbit that has already run away when you may need it to shoot the bear currently hidden from view?

|

Along with the utter failure of traditional monetary techniques, the Fed has also unleashed a series of unconventional acts in money printing and asset price manipulation. The charts below may no longer shock and awe, but they nonetheless continue to provide context into how entrenched the Fed is in the marketplace. With MBS and Treasury purchases probably having exhausted their usefulness, investors cannot help but wonder what asset(s) are next.

|

Suffice to say, it is this state of monetary dysfunction that provides a great deal of anxiety to investors and Fed officials alike.

The U.S. Government: Brother In Arms

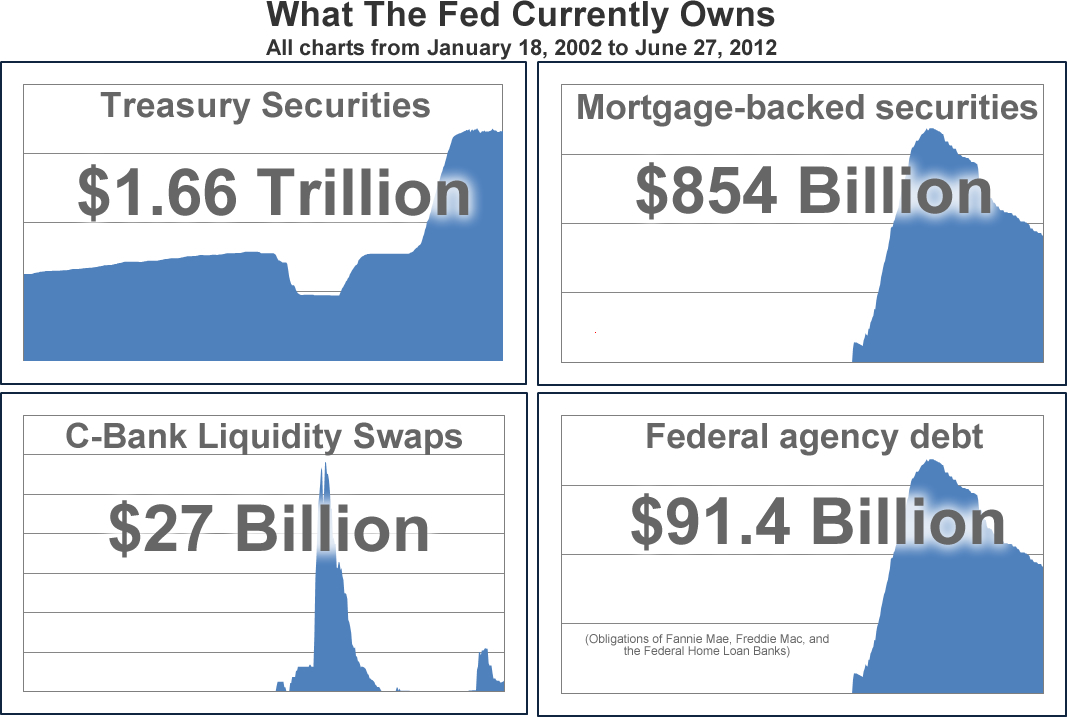

What the staunch Keynesians calling for further government stimulus neglect to mention is that the U.S. government, like the Fed, may be at its conventional limits. Can the U.S. government really be expected to do even more?

|

The U.S. government can borrow seemingly endless amounts of money at ultra-low rates for various reasons, none of which comment on the long-term term fiscal health of America. These reasons, to name three, include handcuffed Treasury purchases from countries that are overly reliant on the U.S. economy (i.e. China), safe haven purchases by investment capital too scared to store their money in euros, and purchases made by the Federal Reserve board. In other words, we all know given the current U.S. dollar centric world that the U.S. government can indeed borrow a lot more if it elects to, but should a government with the U.S.’s fiscal profile really do so?

According to government projections, the total U.S. deficit for the 10-years ending 2017 will be more than $9.2 trillion, with the best 4-years (2014-2017) seeing deficits of more than $600 billion each year. In calendar terms this means that the U.S.’s historic borrowing binge is not even half over. As for the plan to reduce excessive borrowing, there really isn’t any. Rather, Obama’s administration expects individual tax collection in 4 of the next 5-years to be above 60% of the 5-year trailing number, with the highest number coming in 2015 (+80% individual tax increase from 2010). Given that since 1950 individual income taxes have increased, on average, by 42% every 5-years, you have to wonder where all these tax collections are going to come from. Then there are corporate taxes, which have averaged only a 36% advance on a 5-year trailing basis since 1950. Obama expects corporate taxes to advance by 210%, 132%, 151%, and 100% for the 4-years ending 2017 (versus the 5-years prior).

Easy comparisons or not, baring some miraculous combination of a strong turnaround in the U.S. economy and massive tax increases, these tax receipt figures are simply not going to happen. In short, this year’s ‘fiscal cliff’ may be catching all the headlines, but the fiscal abyss that awaits the U.S. government when its forecasts fall apart is significantly more ominous.

The U.S. Is Merely One Example

The recent forecasts from the OECD show that even continued improvement in 2012 and 2013 will not be enough reduce deficits (as a % of GDP) even close to positive levels. When contrasted against the worrisome outlook from the Fed and other economists these figures are terrifying.

|

In the collection of countries highlighted above there are 88-points of reference, with only 6 shaded in blue (no blue since 2007). Thus, government borrowing was in excess before the financial crisis, during, and remains as such after. And the Keynesians are screaming for more simply because interest rates are low?

As for a broader picture of total debt, the figures to anyone lending a smidgen of credence to debt/deficit analysts Reinhart & Rogoff, are downright petrifying. We are not apt to forecast the doomsday too often, but the stats below make you wonder whether the best investments are weapons and food. With the global economy asphyxiated by lackluster growth rates, exiting the deplorable debt trends highlighted below without a sovereign conflagration may simply not be possible.

|

The OECD debt/GDP total is already above 100%, and expected to continue its climb in the years ahead. Then there is Japan, above 200%, which borders on the ridiculous. Perhaps the only positive to be taken from the data is that the ‘euro area’ is expected to be at only 99.9% by 2013 (this lends some credence to the thought that a complete fiscal union in the euro zone could stave off the threats of contagion (i.e. if the U.S. is benefiting because it is the cleanest dirty shirt now why wouldn’t fiscal integration in the euro turn the tables?))

What About Japan?

In spite of these numbers the Japan story doesn’t receive as much attention as the euro crisis. The story goes that the country can continue to defy common sense because its interest rates are ultra-low and a large component of its debt is held by its public.

Unfortunately, this story is slowly being chipped away. To be sure, Japanese people are starting to save less money, the population is aging, and the BOJ recently reported that Japanese external debt is rising at nearly a 15% clip in each of the last two quarters. The time for serious change or risk a crisis may be at hand, which is one of the reasons why newly elected Japanese Prime Minister, Yoshihiko Noda, is trying to double Japan’s sales tax by 2015.

And It Could Get A lot Worse

As if liquidity traps and sovereign meltdown fears not nightmarish enough, another trend seeping into the pessimistic matrix deals with demographics. Specifically, the trend of an aging population.

Some countries have already taken steps to try and alleviate the stress of an older population, most notably Canada, Japan, China, Germany, and others which have or are currently trying to raise their retirement ages. However, as more countries enter an economic slump and governments are called upon to do more stimulating, the expectation of meaningful changes to withstand any future blow from demographic twists is remote. Using Mr. Noda as the example, he is Japan’s sixth Prime Minister in six years, and his tax increase, the first step in combating the debt monster, has not been passed yet.

Needless to say, the worst situation, without question, is Japan. Japan’s old age support ratio was 2.8 in 2008 and is expected to drift to 1.2 by 2050. It is difficult to find anyone that paints an optimistic smile on Japan’s aging trend without the adoption of immediate and jarring policy decisions.

|

Then there is China, where life expectancy is soaring and the fertility rate is plummeting. In 2000 China had six workers for every citizen over-60 and by 2030 there will scarcely be two. By 2050 China is estimated to have more than 480 million people aged 60+ and more than 330 million aged 65+. For a country that has benefited immensely from having a large workforce (see China’s ‘demographic dividend), the sheer size of the country’s growing elderly population will be a major, and perhaps economically destabilizing, development.

As for the U.S., the baby boomers may be getting older and less apt to be heavy equity allocators, but at least the U.S. is replacing its population.

Is The Great U.S. Consumer About To Jump Back In The Game?

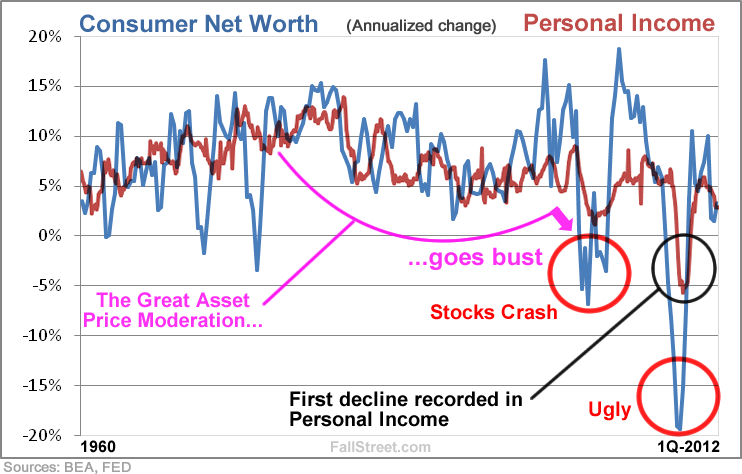

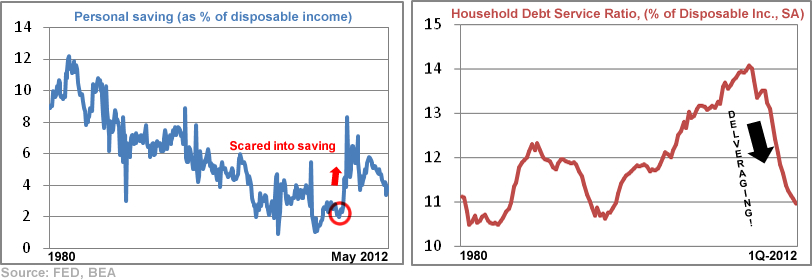

Along with the more popular debt considerations – which show consumer deleveraging still has a way to go - the U.S. consumer is trapped in an exceptionally tight labor market. Not only are many income readings failing to keep pace with government procured inflation statistics, some of the statistics are still collapsing.

|

While most economists rightly focus on the tangibles that are interest rates and payrolls, there is also the observation that the U.S. consumer’s spending capabilities are rooted in confidence and paper asset prices. It would not be a stretch to conclude that 12-years of fantastic ups and down in the markets have permanently altered the consumer’s state of mind (i.e. taking on more debt to buy things isn’t as appealing as when you think your stocks are going to climb 5% instead of say 12% a year).

|

However, all is not completely lost. Rather, thanks to the worst probably being over in housing and an ultra-accommodative Fed (they hope) supporting stock prices via the punishment of bond holders, the consumer may be settling in to an extended period of relative calm. This depends greatly, of course, on what the employment picture looks like.

|

As the above charts aptly demonstrate, the consumer has already taken great strides to deleverage, and savings (after benchmark revisions) are hovering around 4%. Should these trends continue, the case for further consumer deleveraging will, eventually, vanish. This is not to say that a de-levered consumer is ripe and ready to start gorging on debt again. On the contrary, the appropriate analogy is that after having crashed Daddy’s Porsche consumers may soon be asking for the keys to the Scooter. Don’t expect yesterday’s pace of spending and debt accumulation – ever! – but do expect a reassertion of the U.S. consumer.

Conclusions

Those that fret about the bailout policies of yesterday need not worry. If, and more likely when, the sovereign bushfires turn into raging infernos the dangerous dalliance with interventionist policies seen after the 2008 crisis will with hindsight look tame. Quite frankly, the financial world is broken, and the only fix from policy-land is to borrow and print.

In this strange and dangerous world the sole sense of solace comes from the twisted observation that economies and markets are so connected that all boats will be floated if those that can borrow (or print money efficiently) do so with reckless abandonment. The dichotomy, if otherwise unclear, is that the Hayekian spirit that is suppressing bailouts in the name of austerity in the euro zone is non-existent in certain parts of the world. For example, in an annual report on the U.S. economy released this week, the IMF concluded that the U.S. must nullify ‘fiscal cliff’ uncertainties immediately, raise its debt ceiling, and ensure that spending is “as growth-friendly as possible.” This is the same IMF that has been taking a cleaver to their global deficit/GDP forecasts (see ‘Fiscal Monitor’ reports) for much of the last year. Debt may be the problem but, evidently, more debt is the answer.

In short, read any paper on the topic of ‘fiscal space’ and you won’t be able to sleep at night. But as growth stalls these nightmares are forgotten for another day because there is supposedly always room for pro-growth borrowing by key governments. Thanks to escalating government debt loads and the lack of traditional ammo from central banks, the world is more unprepared for the next financial crisis, whenever it should arrive.

BWillett@fallstreet.com